One month ago, a photo of two children doing their homework outside of a Taco Bell, just to get access to the internet, made rounds across social media. The photo and other reports about the lack of internet access have shed light on a glaring inequity in our country. As we move forward in the digital age, WiFi and technology are not luxuries anymore. These necessary tools must be included when we discuss education funding.

In the Bradford v. Maryland State Board of Education, a group of concerned parents, represented by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) and the ACLU of Maryland, are challenging the State of Maryland to meet its obligation to educate our children, by, among other things, closing the digital divide in Black and Brown communities.

During a townhall in July that addressed issues of education equity in Baltimore, community members and students came together to share their own experiences of being disconnected during the school year and to talk about the historic Bradford lawsuit.

Ivan Roberts, a recent graduate of Bard High School Early College in Baltimore, shared a tremendous obstacle to his graduation this past spring. “There came a point in time when my computer broke and there was no second plan,” said Ivan. “I was in a predicament similar to most of my peers. If you weren’t able to complete your remote learning courses, especially if it was a class required to graduate, you’d be unable to get your diploma.” Ivan Roberts was ultimately able to obtain a laptop. But he was lucky—without that laptop, he would not have been able to graduate.

Kimberly Vasquez, a senior at Baltimore City College, experienced something similar. Unreliable WiFi was interfering with her schooling. As a lead organizer of Students Organizing a Multicultural and Open Society (SOMOS), an organization tackling systemic issues of injustice through activism, Kimberly and many others petitioned Comcast with a list of demands to address the significant barriers that she and so many other students are facing during remote learning.

“We cannot advance in technology if people don’t have access to it.”

“Students are being completely and systematically shut off from their education,” said Kimberly. “Ongoing structural disparities continue to perpetuate this problem. We cannot advance in technology if people don’t have access to it. Before with in-person classes, I was a good student. I would be on top of my work. But now with it being all virtual, it’s been really hard mentally. I’m placed in the position where I feel ashamed and embarrassed that I can’t afford high speed internet. I am falling behind compared to my classmates. It makes me frustrated, angry, and sad. After you get kicked out of a zoom call three to four times and miss half the class, you’re so discouraged to even go to school.”

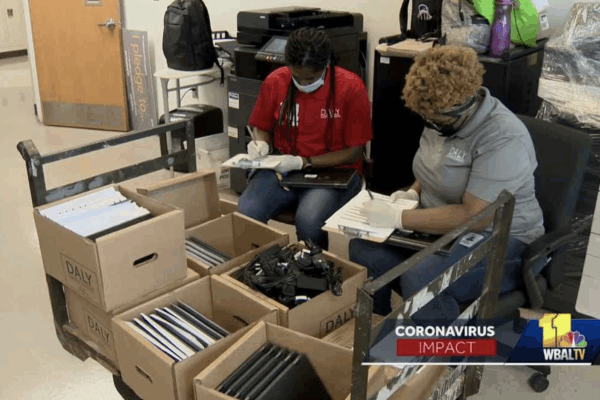

Forty-five percent of children in Baltimore City Public Schools reportedly did not have computers or access to the internet during the remote learning period this past spring. Now, the new school year has begun, and parents are still complaining that their children lack laptops or internet access.

LDF, a civil rights organization that has long fought for racial justice in education, has recently called on internet service providers to do more for Black, Indigenous, and students of color during the current crisis caused by the pandemic. “As our country faces a reckoning with our history of racism, companies can take immediate action to address the longstanding and deeply unjust educational inequalities in school districts all across our country,” said Cara McClellan, Assistant Counsel at LDF.

Internet service is now necessary for students to access their education. Disregarding this reality only exacerbates racial inequities that have existed in education funding for decades. We are calling on the State to ensure that students are not denied their state constitutional right to an education through no fault of their own.

The Alliance for Excellent Education has found that most children without technology and internet access are Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Alaskan Native and are living in rural and/or low-income households. We cannot keep depriving these students of educational opportunities merely because government resources are not being allocated fairly.

Queen Royalty, an avid education activist and an 11th grader at Bard High School Early College, a Baltimore City school, said about the digital divide, “Race equity to me is equal money all around. You can’t put effort in one place and not in another place.”

Over decades, the State has continuously cut and underfunded education, resulting in disproportionate harm to Black children whose schools have historically always been underfunded. The Bradford lawsuit demands that the State meets its obligation to adequately fund education in Baltimore, so students are not forced to learn in subpar conditions and do not miss educational opportunities due to lack of internet access or technology.

Maryland legislators can make an impact by proactively investing in Black children’s schools.

Maryland legislators have an opportunity to act now. The legislative session will begin in January 2021, and state Democratic leaders have already indicated their commitment to overriding the Governor Hogan's veto of the Blueprint for Maryland's Future (HB1300) — a $3.4 billion sweeping education reform bill.

Moreover, given the impact of COVID-19, the legislature will have to rethink the phase-in of Blueprint funding over the planned 10-year period to give greater priority to the most underfunded school districts and to students with the least resources.

Ultimately, Maryland legislators can make an impact by proactively investing in Black children’s schools, which will not only close the digital divide but also promote greater racial equity in Maryland school systems.

Read more about our Bradford lawsuit here.