A Mother Has Waited Half a Century to See Her Son Be Paroled

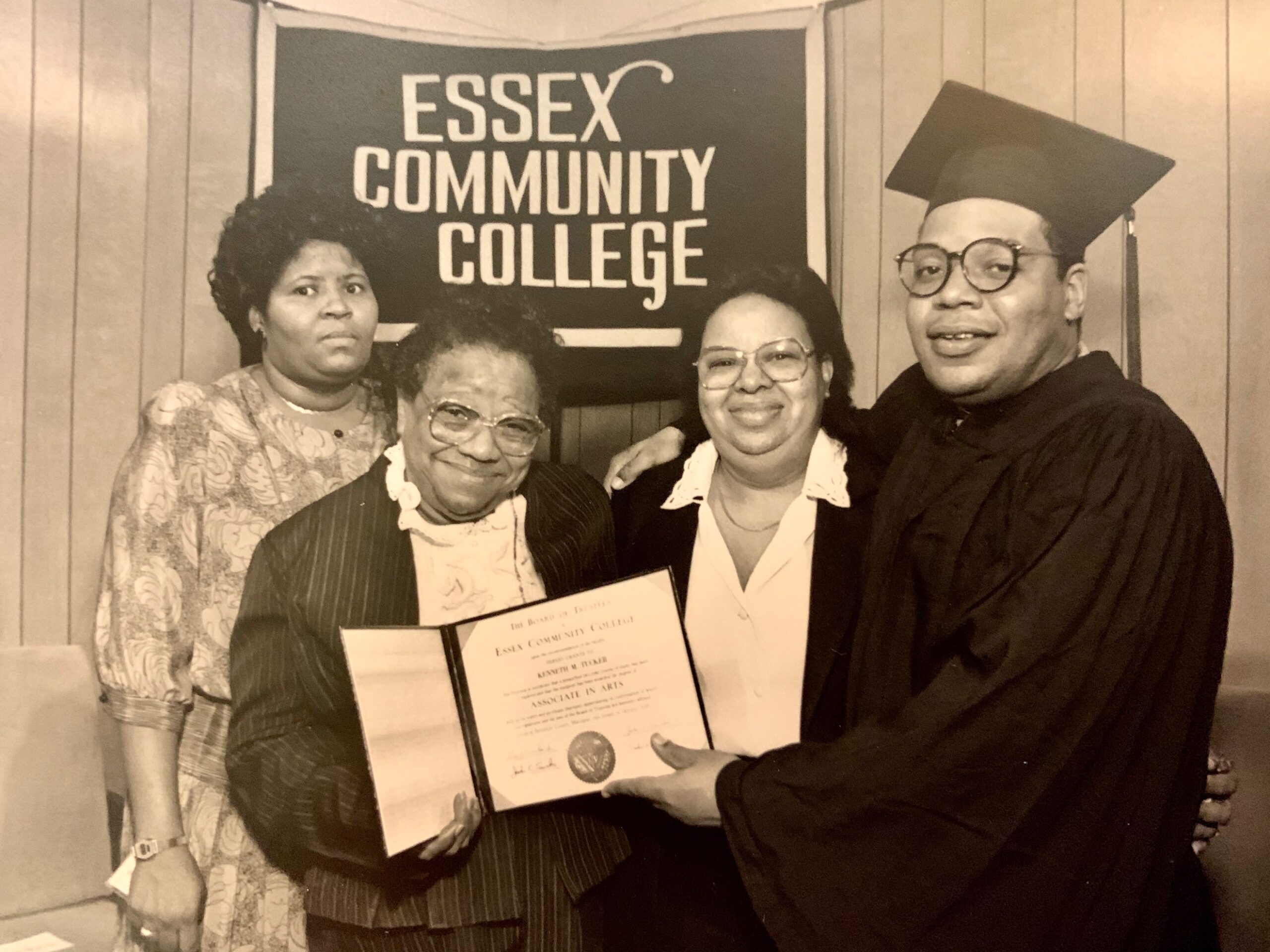

Mrs. Eula Tucker is the mother of Kenneth Tucker. Her son was sentenced to life with the possibility of parole as a child and has been in prison for nearly half a century. While in prison, he has grown, taken classes, earned certificates, and rehabilitated himself. Unfortunately, because of Maryland’s broken parole system, he has not been granted the parole he earned long ago. In fact, he has never even been considered for parole by the only decision-maker in Maryland with the authority to grant someone serving a life sentence parole: the Governor.

“I wasn’t expecting him to be in there for that long,” said Mrs. Tucker. “He was supposed to be paroled after a certain amount of time. It has just been a wear and tear on everyone. Then his father died, so I had no one to take me to him back and forth. And now I have to get to know him all over again.”

Mrs. Tucker described the feeling of not seeing her son outside of prison walls for so many years as hollow. She said: “Almost half of his adult life is gone. We didn’t get to know each other or do anything. Having a loved one in prison, it feels hollow inside.”

In 1995, more than 20 years into Mr. Tucker’s incarceration, Maryland adopted the harsh “life means life” policy that functionally abolished parole for people like him. There is a difference between life with and without parole. Life WITH parole should mean that Marylanders have a real opportunity to redeem themselves and return safely back to the community.

During his incarceration, Kenneth Tucker has established an impressive record of accomplishments in education and scholarship, including obtaining his GED, an associate’s degree, and a bachelor’s degree in psychology. Despite being sent to a maximum-security prison as a child, Kenneth has never had a single infraction involving violence of any kind.

He is an active community leader, a compassionate observation aide for people who are in crisis, a mentor for the University of Baltimore college program, and co-founder of several organizations seeking to improve programming opportunities for people in the DOC. He also helped start a program that teaches sign language in Maryland prisons so that people who have difficulty hearing can better adjust to prison conditions. Kenneth has gone above and beyond rehabilitation. He has shown in multiple ways that he is committed to a new life dedicated to serving others.

When someone has done everything the courts have asked them to do with the promise that one day they would be able to earn release, the government has an obligation to honor that promise of parole. For many, parole is a ray of light. It is the one thing people who are incarcerated can hope for and work diligently towards.

As a child, Kenneth and his mother did everything together. “When he was little, we did a lot because that was my first and only child,” said Mrs. Tucker. “We went to church together. He started school, which was a great adventure. He was on most of the sports team, football and basketball. We were great together.”

After he was incarcerated when still a child, Kenneth and his mother didn’t get to spend more time with each other, but what was a bright light for both of them was the opportunity for parole. That opportunity has yet to be fulfilled – not because Kenneth hasn’t rehabilitated himself, but because Maryland is one of only three states that puts the decision to approve parole in the hands of the Governor, which wrongfully politicizes the process.

Equally appalling is that our state leads the nation in racial disparities in our prisons and jails. We are tied with states like Louisiana and Mississippi. About 84 percent of those serving life sentences for offenses committed as children are Black, even though Maryland’s population is only about 30 percent Black. That is a gross racial disparity.

The bottom line is white and Black children are not treated the same in our legal justice system. So not only are Black people incarcerated at unfair and disproportionate rates, but they are also kept in prison for longer periods of time because of Maryland’s broken parole system.

Thankfully, three Marylanders sentenced while children to life with the possibility of parole – Nathaniel Foster, Calvin McNeill, and Mr. Tucker – along with the Maryland Restorative Justice Initiative, an organization that works for the rights of incarcerated people, sued because Maryland converted "life with parole" sentences into de facto "life without parole" sentences. For Marylanders who were sentenced as children, this constitutes cruel and unusual punishment under Supreme Court precedent.

After five years of fighting for their rights, just this month, they reached a victorious settlement in their case. The Maryland Board of Public Works approved a legal settlement that requires the Maryland Parole Commission, Division of Correction, and Governor to adopt new regulations and policies to help rebuild Maryland’s parole process for those sentenced as children to life in prison.

“With the settlement, we are no longer held hostage,” said Kenneth Tucker. “But more importantly, brothers are now excited about fighting for their liberty. The case has established a movement behind the wall, a fever that cannot be contained.”

Over the years, Marylanders with life with parole sentences and other civil rights groups have made a strong legislative effort to take the final decision of whether to accept the Parole Commission’s recommendation out of the hands of the governor. When paired with this important legal settlement, that law would go a long way towards fixing our broken parole process. These efforts are also crucial steps towards ending mass incarceration in Maryland.

When told about the settlement and the real possibility that her son would be able to return home, Mrs. Tucker was relieved, but unsure. “I’m keeping my praises and thoughts until I see him walk through that door. At 83 years old, I hope to see my son again.”

In 2020, both Mr. Foster and Mr. McNeill were released – Mr. Foster because his sentence was commuted and Mr. McNeill through a judge’s resentencing order. Mr. Tucker hopes to come home soon, too.