When I was a little girl, my mom would tell me my hair was beautiful. And I loved my hair. As I grew up, I would hear from teachers, family members, and society that my natural hair was not acceptable. I, like many Black women growing up, was told you had to straighten your hair in order to have “good hair” and to succeed in this country. Those comments subtly told me that my hair was ugly and by extension I would be ugly and unacceptable if I maintained that hairstyle.

I was in middle school when I got my first relaxer. For those who don’t know what a relaxer is, it is a chemical process that turns curly strands of hair bone straight. The relaxers created scars and scabs on my head. Blood from my scalp would stain my shirts because the chemicals are so strong they can cut through metal.

What frustrated me was that I felt I had to keep coming back to the salon and putting myself through this excruciating process to try to squeeze myself into this Eurocentric beauty mold where I just don’t naturally fit.

When I was 20 years old, I had enough. I cut all my hair off. Going almost completely bald felt liberating, even though I was almost petrified throughout the process. Wearing my hair in its natural state, without relaxers, means freedom to me.

When I decided to wear my natural hair, I received comments from both white and Black people that undermined my feelings of professionalism and worthiness. This is not an uncommon experience for Black women. In one test of implicit bias, white women showed the strongest bias against textured hair, rating it as less professional than smooth hair. This is the subtle racism that Black women have had to face for centuries.

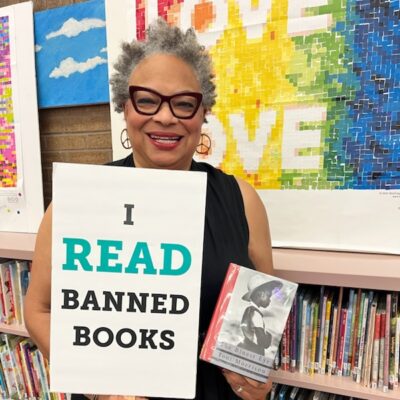

Pictured: Amber Taylor (left) and mother, Rondollyn Johnson-Taylor (right)

While some decisions to have straight hair are purely for fashion, for many, it is about keeping up a very particular appearance, sometimes at the cost of the consumer's health.1 A recent study by the American Journal of Epidemiology determined that the use of hair relaxers may be linked to uterine fibroids in Black women and girls, a condition that is estimated to affect 80% of Black women over their lifetime.2

This is not to say that there’s anything wrong with a Black woman choosing to wear her hair straight. This is about choice. Sadly though, often when a Black woman chooses to wear their hair the way it naturally comes out of their head or use a protective style, she faces discrimination.

Back in 2015, I was turned away from a job because “my look,” referring to my hair, wasn’t “in line with their culture.” People who imagine themselves to merely be upholding professional "standards," standards that too often treat textured hair and protective styles as unsuited for the office and classroom, reveal their bigotry when they consider Black people’s natural hair as “unprofessional”. This discrimination, rooted in a long legacy of racism, white supremacy, and gender bias, remains a harmful practice with severe consequences, particularly within education and employment settings.

Maryland’s version of the Crown bill seeks to ban hair discrimination against common Afro hair styles. The Crown Act is very much needed to legally protect Black people from this type of discrimination, so that Black people can live without fear of retaliation for their natural hair or protective styles. It would say our government is here to protect us against this extension of racial discrimination.

(Amber Taylor testified in front of the Maryland Judicial Proceedings Committee on February 17, 2019, in favor of the Crown Act. Read her testimony here.)

Don’t get me wrong. As a Black woman with natural hair, I fully support the passage of this law, which would make me feel seen and my fears understood. But this bill will not end hair discrimination. However, it might start a culture shift so that as a society, we may understand that however people choose to wear their hair, particularly in its natural state, shouldn’t be deemed as negative. It’s just the way we were born and choose to express ourselves.

As Kyle Barker (played by Terrence Carson) from Living Single said: “My hair is not just 'for fashion’, it's part of my heritage. It is a statement of pride.”

I hope that within a few decades, Black parents in Maryland will not have to tell their children to wear their hair the white way in order for people to see their talents and humanity. And hopefully, the next generation of little Black girls can just wear their natural hair with joy and not fear. I want the next generation to just be able to be in love with themselves and be free to show the world their natural hair.

1Nourbese N. Flint, Teniope Adwumi, Natural Evolutions One Hair Story, Black Women for Wellness, http://www.bwwla.org/natural-evolutions-one-hair-story/ (last visited Nov. 17, 2019).

2Lauren A. Wise, Julie R. Palmer, David Reich, Yvette C. Cozier, Lynn Rosenberg, Hair Relaxer Use and Risk of Uterine Leiomyomata in African-American Women, American Journal of Epidemiology, https://academic.oup.com/aje/article/175/5/432/175919 (last checked Nov. 17, 2019).