News & Commentary

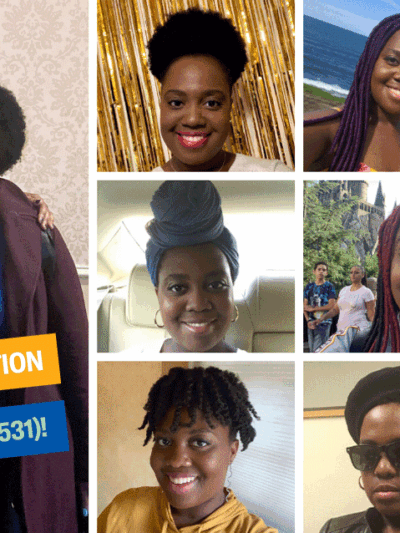

Crown Act: My Hair is Beautiful, Professional, and Acceptable

When I was a little girl, my mom would tell me my hair was beautiful. And I loved my hair. As I grew up, I would hear from teachers, family members, and society that my natural hair was not acceptable. I, like many Black women growing up, was told you had to straighten your hair in order to have “good hair” and to succeed in this country. Those comments subtly told me that my hair was ugly and by extension I would be ugly and unacceptable if I maintained that hairstyle.

By Amber Taylor

How Marylanders are Making a Difference: Lobby Day 2020

Over a hundred people from across the state attended this year’s Lobby Day and demanded action from their state legislators. From Western Maryland to the Eastern Shore, our members demonstrated that one way to make an impact in your community — and our state capital — is through advocating in person by meeting with your elected officials.

One Year After the Police Killed Emanuel Oates: What Still Needs to Change

On February 19, 2019, Emanuel Oates was shot and killed by officers with the Baltimore County Police Department.

On Broken Voting Systems

One of the biggest threats to our democracy is rooted in our mass incarceration crisis. Our nation has the highest incarceration rate in the world, and Maryland disgracefully leads the nation with the highest percentage of racial disparities in our prisons. While Black Marylanders only make up 31% of the overall state population, they represent 52% of people in jail and 69% of people in prison.1 There are serious and continuing problems of over-policing in Black neighborhoods and biased sentencing laws. These racist policies have a devasting effect on the political power of Black Americans.

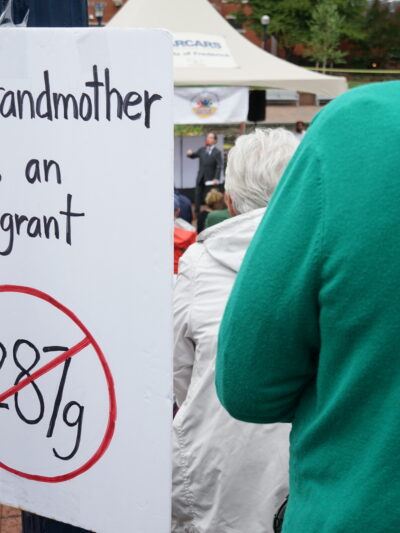

Seven Truths Surrounding 287(g) Programs

Currently, three Maryland counties – Frederick, Cecil and Harford County – are actively using local police agencies to target and cage immigrants for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement as part of the 287(g) program. The 287(g) program deputizes local police as federal ICE agents who receive minimal training and are incentivized to use racial profiling tactics against mostly Black and Brown immigrants. The belief by some that programs like this keep communities safe stem from several myths. Let’s set the record straight.

Please Join Us in Congratulating Our New Board President: John Alvin Henderson

The fifth of six children, John Alvin Henderson was born in Indianapolis, raised in Tuskegee, Alabama, and Silver Spring, Maryland, and traveled far before finding home with his wife and children in Baltimore. Of the city, John says, “there is a sense of community with the place that called to me.” Living his earliest years in Tuskegee, a hyper-segregated city, John has always been aware of the importance of civil rights and community. In fact, what first drew John to the ACLU of Maryland was our commitment to intentionally further racial justice.

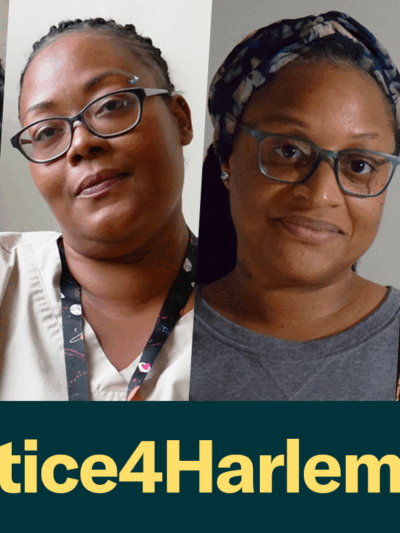

The Lockdown: What happened in Harlem Park would not have happened in Roland Park

On Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2017, at around 4:36 PM, Baltimore Police Department homicide Detective Sean Suiter suffered a fatal gunshot wound to his head, from his own service weapon, in a vacant lot in the Harlem Park neighborhood in Baltimore.

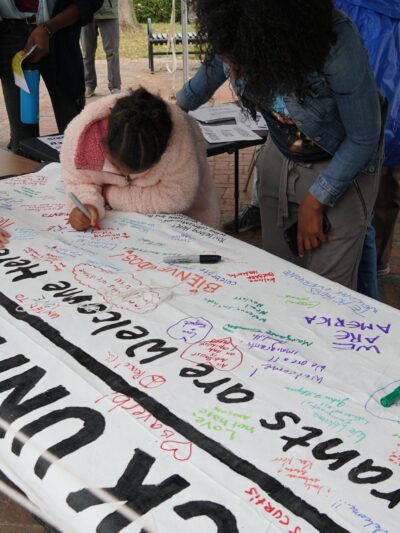

Embracing Our Community

On Tuesday Nov. 12, crowds gathered in front of the U.S. Supreme Court for the “Here is Home” rally, holding signs that read “Defend DACA” and “Let Dreamers Dream.” In the cold pouring rain, protestors cried, “Ni la llueva, ni el ventó, detiene el movimiento,” which translates to neither the rain nor the wind stops the movement.

By Neydin Milián

Latinidad and Persecution

Latinidad is complicated for me. It’s the transgenerational trauma passing through our bloodlines. It’s the constant reminders of the horrors our ancestors suffered and the atrocities some of our other ancestors likely committed. Latinidad is being hurt, learning from our abusers, and subjecting our very own to that same persecution. Latinidad is a violent term in itself: A monolith that erases Black and Indigenous people, it works to silence the experiences of non-white/mestizo people both in the United States and abroad.

By Jay Jimenez

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.